Art for Whom? Examining the Disconnect Between Black Artists and Black Viewers

Plus HBO Rebrands Yet Again, Mubi Takes on A24

Is it just me, or is May absolutely flying by? How is it already the middle of the month?

I’m testing out publishing this newsletter on a different day, mostly because last Monday, I got hit with seven back-to-back Substack newsletters in my inbox. I was in a consultant meeting the other day where someone asked me about the best days of the week to publish, and honestly? I’m not sure it matters anymore. The volume of newsletters flooding people’s inboxes feels like it’s an all-time high.

The best you can do is aim to build a connection with your readers and consistently write pieces that people will look forward to reading—whether that’s insightful information, compelling storytelling or a strong point of view. That said, I’ve noticed more and more people expressing guilt about their ever-growing pile of unread Substacks. Town & Country even wrote a delightfully tongue-in-cheek article about Substack etiquette, and the whole thing is definitely worth a read!

Your inbox is bursting at the seams. Forget back issues of the New Yorker, your shame is now an unread stack of newsletters. It turns out Ronald Reagan was wrong about the scariest words in the English language: There are four, not nine: “I’m starting a Substack.” — Inbox Armageddon: A Guide to Substack Etiquette

This week, I’m sharing an essay on the strange and disheartening reaction to Thomas J. Price’s figurative sculpture of a Black woman recently installed in Times Square. But first, a few news bits I found interesting.

What’s Your Name Again?

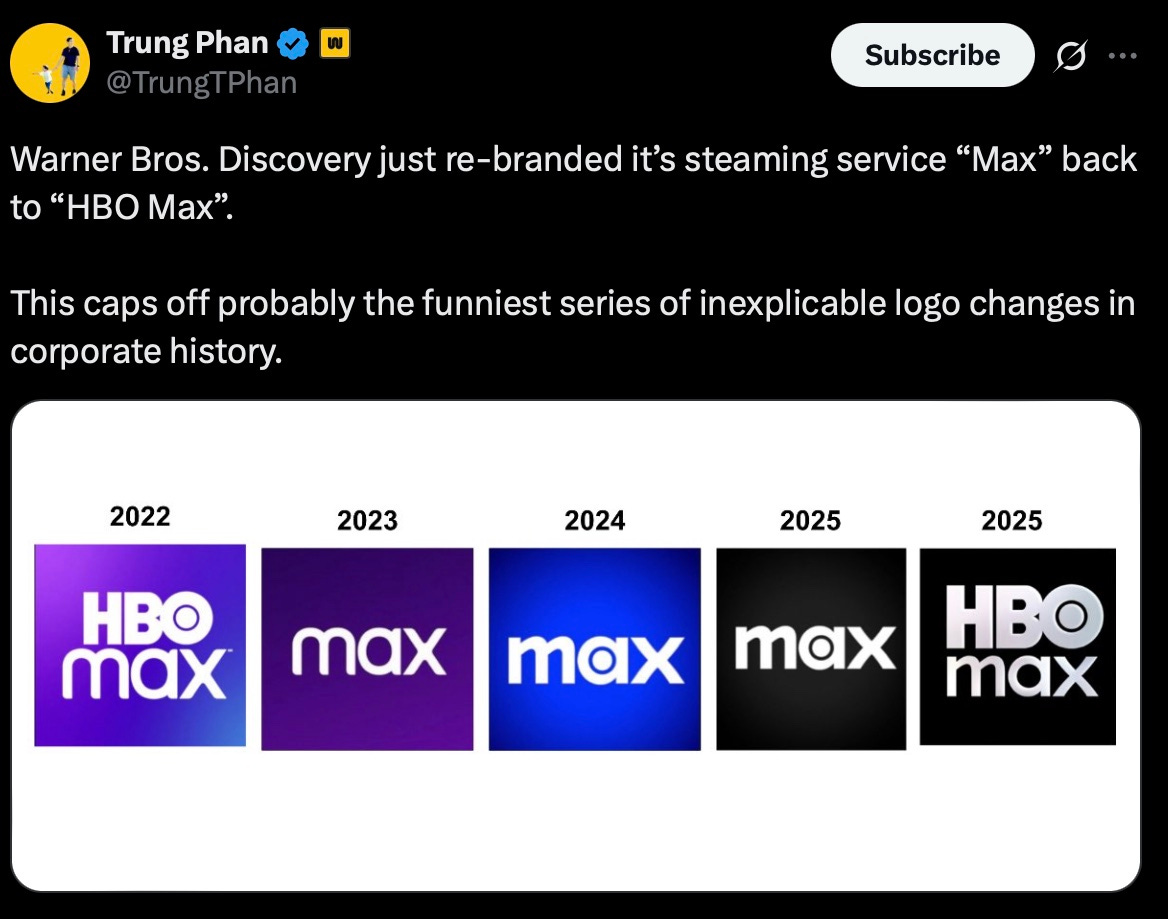

Warner Bros. has once again rebranded its HBO/Max property—and the memes are creative and funny as hell. It’s great that the marketing team was allowed to poke fun at the rebrand; they’ve been posting through it all afternoon and even brought in everyone’s current favorite Max… err HBO Max star, The Pitt’s Noah Wyle, for a skit.

Writer Jeremiah Johnson shared on X, “Had a friend inside HBO at the time and apparently the entire 'Max' branding was one powerful exec who thought it would be a great idea contra every single piece of internal research. Just one singular guy on a power trip.” Which is exactly how you would expect these kinds of poorly thought-out decisions to be made.

The name of this streaming platform has been changed every year for the past four years—it’s already happened twice in 2025 alone! And let’s not even get into the whole HBO Now and HBO Go sagas. Talk about identity crisis.

Casey Bloys, chairman and CEO of HBO and Max content, was on The Town podcast last month talking about the internal decision-making behind the rebrand. They’ve officially moved away from trying to compete with Netflix by being the all-things-for-everyone platform. After conducting focus groups to understand subscriber behavior, they found that what people really value is the HBO programming: prestige dramas, comedies, documentaries, the Warner Bros. movie catalog, and the studio’s TV library. Viewers aren’t tuning in for TLC reality content, home renovation shows, or food programming.

The bottom line is that it’s incredibly hard and expensive to go head-to-head with Netflix and Amazon for a share of people’s media diets. Personally, I find myself spending the most time on Hulu, mostly for its strong indie film offerings and the very entertaining FX TV library.

Mubi Takes on A24 and Neon

Variety has a new cover story on Efe Cakarel, the founder of Mubi, and his ambitious vision for the future of funding, distribution, exhibition and streaming. Mubi gained a lot of press and notoriety last year after stepping in to distribute The Substance, which had been dropped by Universal and went on to earn five Oscar nominations.

Mubi has always been a bit of a puzzle to me—their original pitch of offering one new film a day via a curated online portal was clever. But now, I’m not quite sure what to make of their pricing ($14.99/month), especially given their relatively limited library compared to other streamers. Netflix, for comparison, ranges from $7.99 to $24.99, but offers a ton of content.

That said, Mubi’s emphasis on the in-person cinema experience and community building is, in my opinion, a really smart move. It helps differentiate them from other indie distributors and reinforces their brand as a true home for auteurs and supporters of global cinema.

“I never refer to Mubi as a streaming company,” says Cakarel. “We have our platform, but Mubi’s goal is to bring people to cinemas, and we are releasing our films in theaters and encouraging people to go.”

To that end, Mubi recently launched a magazine and a publishing arm “to put out books about the cinema culture,” and is behind the “Mubi Podcast,” which highlights stories from Hollywood history.

Mubi has also gotten into exhibition even more directly. It is building cinemas in Mexico City and Los Angeles; later this year it will unveil events in 11 cities around the world. “From Chicago to Istanbul to Milan to Buenos Aires, it’s going to be a physical festival where we bring our members together,” Cakarel says.

I think it’s great that another distributor is stepping up to compete with A24. I’ve really liked what Neon has been doing over the past few years, their streaming deal with Hulu is super smart. A24 had a streaming deal with Showtime (RIP), and now it’s moved over to Max, née HBO Max (lol).

The fact that any of us even know the names of these distribution companies is a marketing win. A decade ago, the average viewer didn’t think twice about studio branding, it was insider stuff. But A24 has been leading the charge in marketing itself as the brand, and the films it distributes often feel like extensions of that identity. Neon, on the other hand, seems to put the spotlight on the movies themselves. A24 feels like it centers itself—there’s an “A24 movie,” an “A24 aesthetic”—whereas Neon feels more filmmaker-forward. Did I know who Oz Perkins was before that Longlegs campaign? Absolutely not!

When Black Figurative Art Finds a Black Audience

Most recently, artist Thomas J. Price’s Grounded in the Stars, a 12-foot-tall figurative bronze sculpture of a fictional Black woman, was installed in Times Square, and it’s faced some unexpected pushback. Now, if you told me the backlash was coming from the MAGA crowd upset about “woke” sculptures or whatever, I would’ve rolled my eyes and moved on. But the group finding this sculpture of a full-figured Black woman offensive is... other Black people.

Fatphobia is real, and many critics have questioned the valorization of a woman they describe as looking “sloppy.” Some reactions have been even more obscene. It’s striking to see this kind of visceral response from within the Black community, especially when representational art featuring Black figures—often celebrated by the predominantly white art world—has been gaining accolades and sales for the past five years.

Grounded in the Stars is described as, “A fictionalized character constructed from images, observations, and open calls spanning between Los Angeles and London, the young woman depicted in Grounded in the Stars carries familiar qualities, from her stance and countenance to her everyday clothing. In her depiction, one recognizes a shared humanity, yet the contrapposto pose of her body and the ease of her stance is a subtle nod to Michelangelo’s David. Through scale, materiality, and posture, Grounded in the Stars disrupts traditional ideas around what defines a triumphant figure and challenges who should be rendered immortal through monumentalization.”

My immediate reaction to Grounded in the Stars was: wow, cool! She looks like someone you’d know. Like someone’s aunt or mother. But that’s exactly what some people dislike. To them, she doesn’t look 'put together' enough—her outfit is too simple, her hair not long enough, her body takes up too much space. They don’t like that her hands are on her hips; she’s described as looking angry and therefore reduced to a stereotype, a ‘mammy.’ She doesn’t have the 'right' kind of curves or an hourglass figure. So what’s happening psychologically that makes the accurate representation of an average Black woman feel offensive—or even perceived as a mockery?

I think a lot of misinterpretation around art and artists stems from a lack of knowledge—of historical references and how to interpret intent. I won’t even get into the awful discourse that emerged around Sinners, especially concerning Mary, Grace, and Annie. So much of this bad-faith dialogue is fueled by the internet-driven impulse to comment before doing any research or engaging with the work beyond surface-level impressions, and honestly just plain old misogyny.

Also let’s be real: the art world can be intimidating. Museums, once conceived as centers for learning, often now prioritize display and preservation over education. Rising ticket prices only add another barrier to access.

I’m familiar with Price’s work and had the chance to see one of his sculptures in person last year at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as part of the Time is Now exhibition. What I appreciate about his work is that it features everyday people dressed in modern clothing, holding contemporary items like cellphones. It’s a compelling way to reorient our perceptions of what sculpture can be, and who is deemed worthy of being memorialized in bronze.

Public sculpture has long felt like a medium reserved for men—whether ancient mythical warriors, controversial war generals, conquistadors, or Jesus.

Contemporary artists like Simone Leigh have created powerful motifs that merge the bodies of Black women with domestic objects, highlighting their invisible labor and challenging the ongoing marginalization of Black women's contributions.

Posing modern-day Black figures within historical frameworks isn’t new either, artists like Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas have reimagined canonical works by centering Black bodies within them.

I’m a frequent visitor to museums and galleries, and I make a point to show up when Black art is on view. More often than not, the visitor demographic at those exhibitions tends to be predominantly white. The only times I’ve found myself in a museum or gallery where the majority of visitors were Black were in Washington, D.C.—at the Rubell Museum and at Simone Leigh’s exhibition at the Hirshhorn.

I vividly remember one fall afternoon when my cousin and I visited a gallery in Chelsea, NYC for an exhibit by a prominent Black portrait artist. We were the only two non-white people in the room and it was packed. This artist had garnered a lot of media attention and institutional support, but as we walked around, we couldn’t help but comment on how rushed the work felt. It looked like the gallery may have fast-tracked the show to capitalize on the post–George Floyd protest moment. I’d seen earlier work by this artist and the difference in technique was noticeable—the style was consistent, but the execution and rendering of the subjects didn’t feel as strong.

I really wanted to see Nick Cave’s show at the Guggenheim in 2023, but the day I tried to go, the line wrapped around the block. My boyfriend ended up buying me the exhibition catalog instead, and as I read through it, I seriously wondered who it was written for. The language was extremely academic—ironic, considering Cave’s inspiration for his Soundsuits is deeply rooted in working-class Black culture. His work incorporates sewing techniques he learned from his grandmother and aunt, yet the text in the catalog seemed written for a very different, more elite audience.

The art world has long struggled with speaking plainly. How can visitors truly engage with and learn from the work if the reading level of the materials is geared toward academics? That said, I’ve noticed some recent improvement—many museums seem to be simplifying the language used in wall texts and catalogs, at least based on the recent exhibitions I’ve attended and publications I’ve purchased.

All of this is to say: working-class Black people often aren’t the ones engaging with contemporary Black art, which is a real shame. I wonder if these exhibitions felt more accessible, would Black artists receive more diverse, maybe even flawed, but more meaningful critique—like what we’re seeing with the public reaction to Thomas J. Price’s piece?

Artists who’ve centered Black figuration have become highly collectible and widely exhibited over the past five years, but we rarely hear from everyday Black people about what—if anything—these works mean to them, or how they feel about this kind of representation. Would the people critiquing the Thomas J. Price piece also feel that Kerry James Marshall’s figures are too Black? Or that Henry Taylor’s portraits of his neighbors and friends aren’t beautiful enough?

The controversy around this piece is disappointing, to say the least. But to me, it highlights how far we still have to go in connecting contemporary Black art to Black audiences—especially working-class ones. The fact that Price’s sculpture was installed in Times Square, where people from all walks of life can see it, matters. It had far greater visibility than it would have tucked away inside a museum behind a $30 ticket.

Until next time! Thank you for reading.

As former [redacted] employee, that HBO story almost made me commit a crime. Also, it’s no coincidence you see black people at museums in DC considering that all museums are free here and do constant community events! If you build it, people will come!

Great writing. The HBO/Max thing is so ridiculously funny, especially considering how the thing started with one person's need for relevance, it seems.

The commentary from Black people around Grounded In The Stars has perplexed me, but sadly, I'm not too surprised. It seems that no matter how strongly we want to be seen and left to "be ourselves" in all manner of public life, there's always a voice whispering with a hint of respectability politics, "Ok, you go ahead and be Black...but not too Black". Be Black, but just not "regular" Black (whatever that is). That's what I'm getting from a lot of the commentary. The woman depicted is just too much of a regular, everyday person taking up space. She's not a celebrity and doesn't look like someone's idea of a "successful" Black woman. That sculpture would have been boring as hell, in my eyes.

On the other hand, haven't we been trying to be seen and accepted just as a regular people like anyone else? It's the catch-22 of being Black here (and elsewhere) because no matter what we do, there's always going to be someone who thinks we're not even human. I, for one, welcome Price's depictions of everyday-looking Black people existing in space and just being regular human beings. It's kind of sad seeing the negative reactions to this piece, but with some of the roadblocks you mention, like the studio-gallery-museum pipeline, the cost of access and devaluing of arts education in schools, it's almost inevitable.

People are entitled to their opinions about art and I'm glad that the placement of Price's work in the most most diverse public spaces in the country is sparking conversation, at the very least.